Deadstock: The Rise of Sneaker-Mania

Boyang Hou

The roots of contemporary sneaker culture can be traced back to the mid 1970s in the Bronx borough of New York City. Though celebrity athletes had been associated with sneaker branding since Chuck Taylor endorsed the Converse All-Star in 1921, the 1970s brought a new wave of sneaker endorsements by basketball greats such as Kareem Abdul Jabaar, Julius Erving, and Clyde Frazier. The leading basketball shoe brands released ‘signature’ models for the most elite athletes and these shoes quickly took on the aura of their celebrated namesakes.

Now synonymous with greatness and athletic cool, the signature basketball shoe was embraced by the burgeoning 1970s Hip-hop community both for its utility and its style. B-boys and girls (breakdancers) began to coordinate their clothes to match their sneakers, privileging the shoe as the central object of fashion and launching the basketball shoe’s transition from the hardwood court to the speckled concrete. Basketball attitudes and hip-hop style converged and, before long, the wearer of the signature sneaker became an ambassador of a new lifestyle and cultural identity.

1970s New York is sometimes described as a culture of ‘straphangers,’ a term derived from the hours that city residents spent hanging on the bus and subway straps of NYC public transit. From this position, New Yorkers surveyed eachother’s footwear and paraded their own. Sneaker choice became a statement of individuality as well as vehicle for connecting with mass culture from a place of limited means. It became vital in street culture to sport a quality pair of shoes and to keep them looking ‘fresh out the box.’ 1970s sneaker design offered limited variety, so attention turned to the details. The brand one donned was, of course, important but so were other concerns such as: Was the shoe made of leather or canvas? Was it a high top or low? Would you wear shoelaces and if so, what kind? The color-blocking on a sneaker needed to match other items in one’s gear. Minute customizations such as fattened laces became staples. The sneaker had made its transition into an object of fetishized consumption.

In the 1980s, as Americans reached new heights in personal wealth, those in the middle and upper classes initiated a boom of consumer spending. Athletic endorsement deals became even more lucrative for both footwear companies and athletes and the ideas of athletic idolatry, brand consciousness, and celebrity became even more tightly entwined. Many of the new basketball stars had emerged from lower-class communities and members of these communities began to venerate signature sportswear just as they did their homegrown heroes. Wearing a shoe that an NBA star wore nightly on national television gave fans a direct connection to their idols. Consumers could own a piece of the success of their heroes.

As sportswear fashion rose in popularity, pop culture began to take notice. Artists in hip-hop, who saw international exposure in the early 80s, began to realize that they could leverage their growing influence to negotiate marketing deals with major brands. In 1986 members of the rap super-group Run DMC became the first musical artists to be sponsored by a sportswear company. The group monetized their iconic look (that included Adidas Superstar sneakers) by formalizing a million dollar endorsement deal with the brand.

Air Force 1 High

1986

This fusion of footwear and hip-hop added fuel to the sneaker-mania fire and inspired an explosion of sneaker demand in upper Manhattan. At the center of this explosion was the Nike Air Force 1, a shoe with a 30-year history and essentially no money allocated to its marketing. The Air Force 1 premiered in stores in 1983 and spent only one year on the market. In 1986, Nike reissued the shoe in two stores on the East coast, one of which was in Harlem. Practically overnight the shoe became a symbol of uptown New York identity. Players in the infamous Rucker Park city basketball leagues and tournaments wore them in games. In the street, Air Force 1s became the go-to sneaker of drug dealers, hustlers, and gangbangers. To this day the Air Force 1s are known colloquially as the ‘Uptowns’.

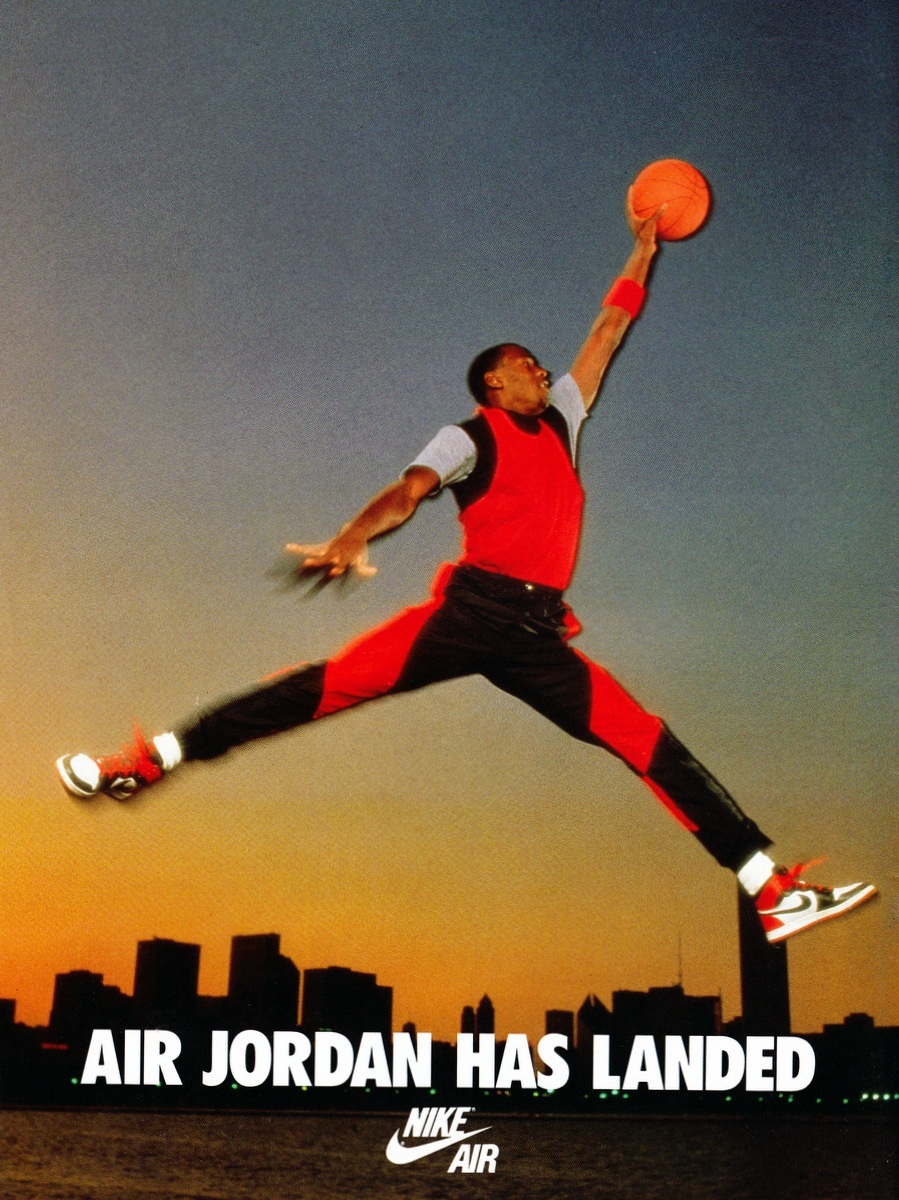

In 1985, as sneaker culture was coming into its adolescence, the doors were suddenly blown wide open. Nike’s historic partnership with Michael Jordan and the release of the Air Jordan 1 pushed the brand miles ahead of the pack. The original sneaker was produced in a color-way prohibited by the NBA and the organization fined Michael Jordan $5000 for every game in which he wore the shoes. Nike paid these fines and Jordan continued to play in his signature sneaker throughout the season. Jordan’s disregard of the NBA ban gave his shoes a rebellious edge and cemented the credibility of Nike shoes (and Jordan himself) as an embodiment of the hip-hop attitude.

With Air Jordan, Nike also introduced the concept of the serial release. Each NBA season opened with the release of a new signature Jordan sneaker. Suddenly, having one pair of Jordans was no longer sufficient. The consumer needed to obtain each new season’s creation in order to stay relevant. The shoes were designed using the most up-to-date technology and produced using luxurious fabrics and materials never before seen on sneakers. These innovations, coupled with inventive marketing strategies by the young ad firm, Wieden+Kennedy, and legendary performances by Jordan on the court, transformed the Air Jordan into a powerful luxury good. To the consumer, the Air Jordan became a surrogate for Michael Jordan himself. Embodied within the shoe were his accolades, his gifts, his charm and charisma. The sneakers connected the masses to the supreme icon. By the early 90s, 1 out of 12 Americans had at least 1 pair of Air Jordans.

The exclusivity of signature performance sneakers like the Air Jordan created a powerful brand, valuable in currency and street credibility. Classic silhouettes of signature shoes were endlessly re-imagined with thousands of new color-ways, graphics and materials. Popular models such as Air Jordans, Air Force 1s and Nike Dunks were given a variety of treatments. In 2005, designer Jeff Staple collaborated with Nike to create the Nike Pigeon NYC Dunk. This shoe, a variation on the classic Nike Dunk Low using the feather colors of a typical NYC pigeon, was in such high demand and short supply that it caused a riot in New York City when it premiered. Nike had strategically limited the release to create hype and, thus, command brand loyalty. The limited release meant huge success on the secondary market as well. Nike’s suggested retail was originally $69 but on the day of the shoe’s release, listings on eBay rose to $750 and eventually topped out at $2000.

During the early 2000s, as rap and hip-hop began to dominate the mainstream, commercially successful artists looked back to the classic sneakers of the 1980s as a means of affirming their credibility and signaling that they were in touch with their roots. Hip-hop legend Shawn Carter, aka Jay-Z, was known to wear a brand new pair of white Air Force 1s each day as a celebration of his own success. His prominence as an artist and trendsetting sneaker enthusiast brought the Nike shoe back into the limelight of youth culture. In 2002, Nike sold over 15 million units of the Air Force 1, a feat made even more impressive since the shoe remained one of Nike’s least commercially advertised. Remarkably, Jay-Z became one of Nike’s most influential promoters without ever receiving a deal.

Jay-Z did receive a sneaker deal in 2003 when British sportswear brand Reebok signed him as the first artist endorsed for the new ‘urban’ division of the company known as RBK. When the ‘S. Carter’ shoe line premiered, all 10,000 pairs sold out in one hour. RBK went on to sign rapper 50-Cent, and later other prominent hip- hop personalities. Due to his celebrity status and high marketability, 50-Cent’s sneaker line went on to break every previous Reebok sales record in the two months following its release, and within four years the company registered a sales increase of 350%. By current estimates, the sportswear industry is an over 26 billion dollar market with about 800 million dollars in sales from shoes alone. The lifestyle brand has become so essential that only 20% of all annual sportswear revenue comes from performance-based athletic models.

The cultural significance of athletic footwear has far surpassed the realm of sport. To some, the sneaker is the quintessential symbol of the contemporary cosmopolitan. To others, it is an overhyped commodity that exploits urban subcultures for commercial gain. For the real ‘sneakerhead,’ though, the sneaker is an art object. Wrapped in paper in the original cardboard packaging, the sneaker is not just a symbol of, but an actual piece of greatness. The sneaker confers onto its owner all of the significance of its history. It’s no wonder, then, that many of the most desirable shoes are never worn. They are collected and appreciated as objects in their own right. They remain in mint condition, carefully wrapped and protected from light. Deadstock.